Part Three: Black Power, Black

September, and Black Africa : the Olympics

during the Cold War

The second half of the twentieth century

witnessed a number of political conflicts which found themselves fought out

under the Olympic rings. The 1968 Games in Mexico City South Africa United

States and the Soviet Union

engaged in tit-for-tat boycotts of each other’s Games. On each of these

occasions, the response of the IOC was to reassert its apolitical character,

which meant in practice that it called for the suspension of all political and

social conflict which might interfere with the running of its showpiece event.

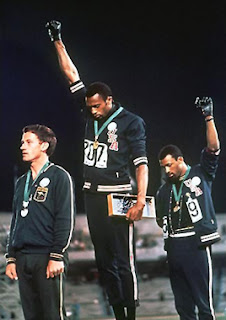

That

salute.

As with its dealing with the Nazis before

and during the 1936 Olympics, the IOC’s professed political apathy caused it to

sacrifice any moral compass in favour of bringing as many of the world’s

regimes under its banner as possible. Under Avery Brundage’s tenure as its

President, the organisation brought the Soviet Union and its satellites into

the Olympic fold despite their shameless flouting of the ban on

professionalism, tried to please both sides of the Beijing-Taiwan conflict over

Chinese sovereignty, and held off for as long as possible international

pressure to exclude the racially-selected sporting teams of South Africa and

Rhodesia. When the IOC voted in 1972, against the wishes of its President, to

bar Rhodesia

Although the Olympic movement during this

period operated in a world radically different from that which existed in the

first half of the twentieth century, many of the old sporting certainties

remained, and the world of Tom Brown’s

School Days was still the vision of sport adhered to by the keepers of the

Olympic flame. In the 1972 Winter Games at Sapporo

No comments:

Post a Comment