After rising through the ranks of various

national and international sporting bodies, not to mention the ruling party in

General Franco’s Spain , and

serving a stint as his country’s ambassador in Moscow U.S.

With Samaranch at the helm, the Olympic

movement became a model of neo-liberalism: television rights were maximised,

the efforts made by bidding city authorities to suck up to the IOC reached

ridiculous proportions (resulting in various bribery scandals), and funds were

diverted away from activities which didn’t earn a profit (eg. the Paralympics,

which receives less funding than the IOC’s stamp collection). The IOC exploits

its coubertiniste heritage to endow

it with moral respectability: it likes to be seen leading the fight against

performance-enhancing drugs or uniting the two Koreas

Juan

Antonio Samaranch: franquista-turned-neoliberal.

By awarding the 2008 Summer Games to Beijing , the IOC completed a dubious hat-trick: it had

awarded its showpiece event to the three most murderous regimes in human

history (after Berlin in 1936 and Moscow

The Olympics don’t need to be held behind

the Iron Curtain or the Great Firewall to be sites of political repression. The

use of force by authorities against those who disrupt their self-congratulatory

carnival has become a feature of every Olympiad, and even in liberal

democracies, the full force of the national security state is thrown behind the

goal of protecting the Olympic brand. Prior to the Vancouver Games in 2010,

Canadian authorities detained journalists who questioned the purpose of the

Olympics. (Australia wasn’t immune to this either – I can still remember former

Democrats’ Senator Andrew Murray’s passionate defence of civil liberties

against the calls of the Howard government for the passage of ‘shoot-to-kill’

laws in the run-up to Sydney 2000.) With the reputations of entire nations on

the line, the logic of neo-liberal capitalism (which, despite its free market

rhetoric, is more accurately termed neo-mercantilism) allows governments to use

the hosting of the Olympics as an excuse for a bit of old-fashioned

authoritarian social control.

The run-up to this year’s London games has

witnessed all the usual hallmarks of Olympism: the displacement of the little

people whose existence gets in the way of the technocrats’ plans for all-seater

state-of-the-art facilities (probably to be torn down after the Games anyway),

the use of anti-terror-style legislation to prevent disruptions by protestors,

and the use of the spectacle by tin-pot demagogues to make some political point

or other (eg. Mahmoud Ahmedinejad, who threatened to boycott London because the

‘2012’ on the Games’ logo looked too much like ‘ZION’). The push for a single UK

When the athletes parade around in the

Opening Ceremony and ‘Er Majesty proclaims ‘let the Games begin’, we would do

well to remember the victims of Olympism: the People’s Olympiad participants

who died in the Spanish Civil War, the Jews and others massacred because of the

political capital granted to Hitler by the staging of the Berlin Games, the

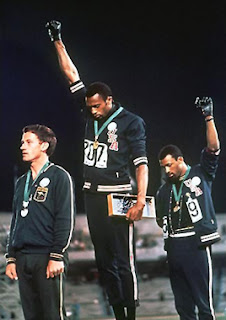

students killed in Mexico City in 1968, and the Georgians killed by Putin’s

goons in 2008.